REVIEW: GERHARD RICHTER AT FONDATION LOUIS VUITTON

Text by ANA ESCOTO

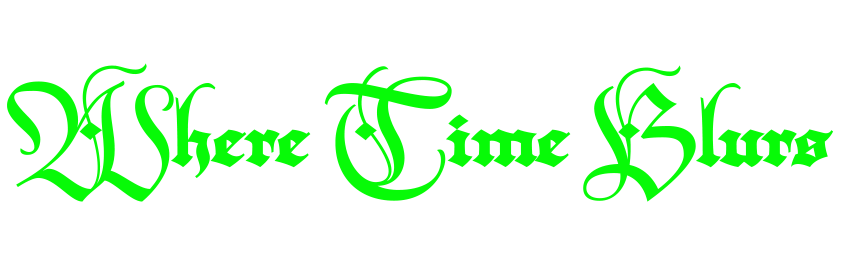

Installation detail, Gerhard Richter, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Emma (nude on a staircase), 1992, oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the author.

I must confess I was somewhat oblivious to Richter’s initial practice. He first came into my consciousness when I was around twelve years old, when I read The Perks of Being a Wallflower. The first time of many. Teenage Riot by Sonic Youth was constantly name-dropped in it, and being the perpetual sponge that I am, anything mentioned in a book I ever loved was worth checking out. That’s when I first saw the infamous candle, which to me held no more meaning than now being the cover of the anthem of my early teens.

This in itself always provokes a twinge of nostalgia in my heart—just remembering how I listened to this song on the school bus, convinced that no one else in my friendship group would understand how it made the world seem dangerous and justified my angst at being on a bus at 6:55 a.m.

Installation view, Gerhard Richter, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Kerze, 1983, oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the author.

I never delved much into Richter’s practice. I, like everyone, knew him for the candle and for the mega canvases drowned in a multiplicity of stripes that didn’t really say much to me. I even handled one of his candle iteration prints at a gallery in London — name redacted — where I used to work. It was a beautiful work, one I knew was created in honour of the victims of the bombing of Dresden, Richter’s hometown, reduced to ashes during the war. Still, at the time, I only grasped it on a surface level.

I also knew that, inevitably, as a German artist born in the 20th century, Richter would be marked by the war. Its devastation runs through the German psyche like thick tar. But the tenderness with which he approaches something so vast and violent is what struck me most, pulling me inward toward my own sadness.

Installation view, Gerhard Richter, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Zwei Liebespaare, 1966, oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the author.

Richter copies film photographs of his family members who were displaced, disappeared, or exterminated by the war, and with a delicate brush dipped in water, he swishes over the lines and creates a translucent veil that blurs the figures. The effect of this varies greatly depending on the subject captured in the photograph.

Richter’s family was torn apart by war. His aunt was brutally exterminated as part of the Nazi eugenics programme for having schizophrenia. Richter captures her youth, holding the artist as a baby. The blurriness of this portrait feels like a premonition of the disparaged future awaiting her. His uncle Rudi, drafted into the Wehrmacht and killed almost immediately on the frontlines, smiles at us in his terrifying uniform. Through the thickness of the blur, there is a sense of ominous darkness—both of what he is about to do and what will be done to him.

Installation view, Gerhard Richter, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Tante Marianne, 1965, oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the author.

The chronological nature of the show, although a device often overplayed, works here to forge a narrative of the themes that crossed Richter’s life more effectively than anything else. The war devastated Dresden, his birthplace, when he was just twelve. There is an evident attempt at reconciliation with the trauma of loss. This continues throughout the decades of his career, always applying the blur as a tool to signify an ominous future or a tragic outcome. Another example of this appears in the portraits of the nurses murdered in Chicago, which he painted in YEAR. These images show eight bright, hopeful faces, photographed on their first day of nursing school. They are buried beneath the veil of the blur; a tragic outcome awaits them, and they will soon become memories of a distant past.

Installation view, Gerhard Richter, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Eight Student Nurses, 1966, oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the author.

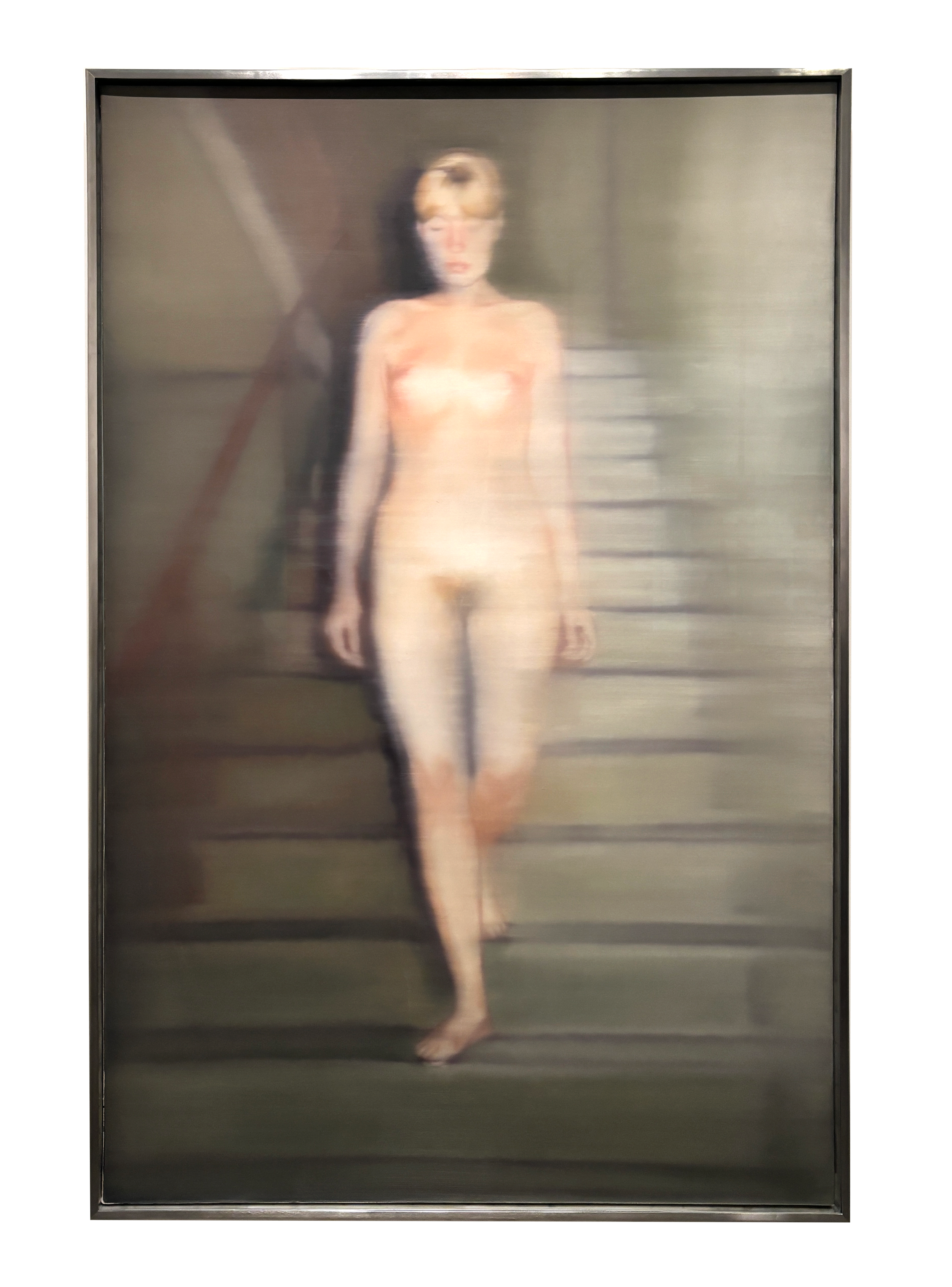

But this blurriness can also feel like an embrace. Like the first vision of a mother through a newborn’s eyes. As Richter moves into the era of husbandhood and fatherhood, the veil becomes one of awe, holding within it a sacred sweetness that intimately covers the scene. His first wife descending the stairs becomes an angelic vision. The back of his newborn’s head is softly cradled in an embrace of warm light brought on by the blur. A picnic with beautiful friends looks the way a memory does when you close your eyes to imagine it.

Installation view, Gerhard Richter, Fondation Louis Vuitton, S. with child, 1995, oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the author.

I was born with a sadness that I cannot escape. I am sensitive to a fault. There is never a time when I am not thinking about how things will inevitably end. Even as a small child of five, during my family’s biannual beach holidays, all I could think about was how many days of paradise we had left before it ended and we returned to our mundane lives. Now, as an adult living far away from my family, whenever I visit them I grieve the moment I will have to leave again. I am heartbroken every time I go back. I cannot escape the feeling that I am living inside a memory, that every instance of my everyday life is a blurred picture of my loved ones.

Installation view, Gerhard Richter, Fondation Louis Vuitton, I.G., 1993, oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the author.

This show made me feel as though I was looking at the components of time itself, in all their elasticity, compounded into one place. Past, present, and future entwined seamlessly into a narrative of heart-wrenching family history. It is no wonder Richter has been consolidated as one of the most important artists of our time. Seeing through his veil, into his soul, was a beautiful experience—one I invite anyone who can to witness.