a conversation with isaac willis - Text by Jael Arazi

Birds of Prey, Oil on aluminium copper, brass and silver solder mounting. Image courtesy of Isaac Wills.

Painting today is often saturated with fragmented, collaged imagery in a way that reflects our contemporary culture’s persistent exposure to fast, digital snippets of visual information. Within this context, what stands out about Isaac Willis’ paintings is their use of different kinds of images, contrasting and combining geometric lines with cropped fragments from historical, Early Protestant paintings. From the slope of a forehead, a dame’s vacuous eyes, to a decorative marble floor, to cartoonish characters and sculptural elements, his constant referencing expands the depth of field of his images. Under the rubric that contemporary painters are the new storytellers of our fractured world, I chatted with the Glasgow-based painter to figure out which stories he intends to tell through his work, and what role digital culture - as the main stage of today’s visual world - plays in them.

Skewed, Oil, epoxy putty on aluminium. Image courtesy of Isaac Willis.

Isaac defines his practice as “image-based” and rejects the figurative/abstract dichotomy. The various references that make up his intuitive iconography develop out of his consideration of painting as a conceptual medium, a platform for experimenting with History as a discipline, questioning and re-evaluating the power of images; ‘I approach painting – all painting – with a pretty deep suspicion over its power, how it’s used.’ With the awareness that, historically, mankind has used the pictorial as a channel to understand and translate the world, Isaac chooses examples from a specific time in history, when art was secularised for the first time and became a conveyor of the Western viewpoint of ‘people being above everything else’, the very roots of the capitalist system that shaped the society we live in today.

Protestantism, Mercantilism, Fetishism, Oil on aluminium, brass, copper, silver solder. Image courtesy of Isaac Willis.

Abstracting this line of thought even further, Isaac plays with the classical idea of painting as a window and bringing its objecthood to fore by applying the props ‘to support paintings so they’re materially aware of themselves.’ The different elements are the result of a process that is part intuitive and part researched, ‘so that leaves some coincidence in how these objects pair, how they influence the different readings. I think when they work best they divert the meaning of the painting … I find this generative in terms of making new ideas.’

Unexpected connections are central to Isaac’s work and even more, they activate it. By mixing older and newer references, he creates time-travelling frames between different moments in history, highlighting and compressing the gaps at the same time: ‘there’s this distance [with] that window that you see of this very old painting but it is brought into this space which is very current and flat and relevant I think.’ Every crop, line, diagram or cartoon of his paintings, of all paintings in Art History really, is ‘being referenced by and references everything that came before it and everything that happens after it.’ All these intuitive connections, the layering of elements and meanings intentional and not, make of painting a network ‘earlier than the Internet.’

Betwixt, Oil on aluminium. Image courtesy of Isaac Willis.

To show that painting has been an instrument to convey power structures and ideals, Isaac uses crops from Old Masters paintings. To say that images conceptualise reality, he employs physics diagrams. And to speak for the way this continues today, he transposes his internet-based research by decontextualizing specific elements from it, especially those originating from some of the problematic corners of the internet culture substratum. The cartoonish Viking men with their ‘funny horn helmets’ in works like Citadel, for example, speak to ‘how Viking imagery is used contemporarily and on the internet – it’s quite scarily the domain of the alt right and white supremacism, it is just crazy.’ This painting in particular is a testament to the manipulation of history through the image, at the core of visual culture, not only due to the Vikings but also the horse props underneath the picture plane, a reproduction of the Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius, ‘almost the original Roman horse sculpture, the OG.’

Citadel, Oil and silverpoint on aluminium. Image courtesy of Isaac Willis.

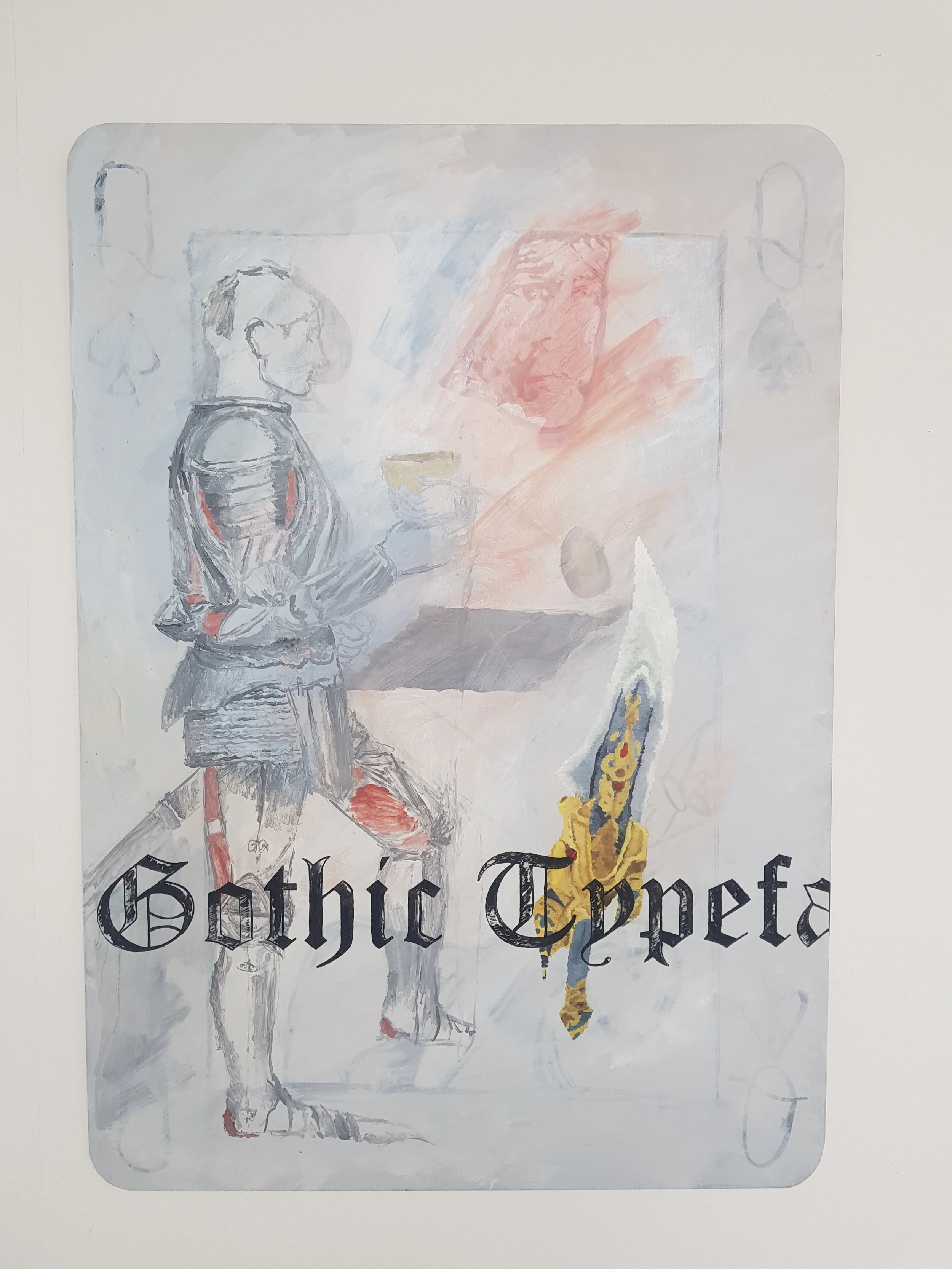

Historical characters who’ve disappeared from modern society become the object - like everything else available online - of a perpetual meme-baseification process. It is the case for the Vikings and medieval knights, like the ones who appear in Gothic Typeface. Medieval memes are curiously popular today, following a similar trajectory in the way they popularise characters and tropes that were originally developed on the margins of books, decontextualised and actualised to convey contemporary messages and ideas.

‘I don’t think memes are bad at all. I think they are an amazing resource for thinking about painting; they’re so laced with references and only understandable by a certain amount of people and I think that’s the same for painting – that’s the network I was thinking about.’ Of course, this process is not new. Medieval knights, and courtesan society more broadly, were famously romanticised in Victorian society, transformed too into archetypes as protectors of power and conveyors of the values transposed onto them by later ideologies. What the internet adds is a broader access to history and art and the tools for the intuitive creative reworking of these materials.

Anonymous, 13th century. Image extracted from @weirdmedievalguys, posted July 4, 2023. | Isaac Willis, Gothic Typeface, Oil on aluminium. Image courtesy of Isaac Willis.

From internet-based research, an internet-based lifestyle, down to the very references he employs, internet culture marks a strong presence in Isaac’s painting. Curiously, there is even an overlap in the way they both function. Isaac elegantly plays with visualising the web in both the metaphorical and literal sense, for example in Domain. Beyond this, however, Isaac de-abstracts this network, be it painting or the Internet itself, making it visible through manifesting the medium’s objecthood and structures, tautologising it. He paints about painting as a conceptual medium, not according to formalist and modernist traditions, but in the contemporary key of the Internet, by pointing to it as one of the most contemporary agents of our everyday lives.

Domain, Oil on aluminium, oak gall ink. Image courtesy of Isaac Wills.

This plunge into Isaac’s practice reveals not just a suspicion towards the image as an instrument of power, but also his peculiar ability to ‘[refuse] the image, while also using it.’ This refusal is the sensation one experiences when confronted with his work; it cannot immediately be put into words. But such confusion is not an issue for Isaac, rather it is the strength of his artistry. When asked about the juxtaposition at the heart of his work, he responds simply, ‘that’s good for me, because that means it’s working.’